You need to laugh ? Well, try these (Links are in black) :

Disney ladies from last night and Disney gents from last night, because nothing will make you laugh more than screencaps from Disney movies and drunk texting.

Want to dress like a Disney character ? Welcome to DisneyBound.

An author AND sarcasm ? Boom.

Harry Potter humor ? Have some !

Love cats ? Yep, click there.

You're into superheroes ? Yes, I know.

Ever had regrets on your drunk texting ? I bet they do.

dimanche 18 mai 2014

The Fall of the House of Usher, Edgar Allan Poe (1/2)

Since I have things to share from the classes I had this year, I decided to keep going with the "studies" material.

I just seemed to me that it could be interesting to share that kind of things, so I told myself "why not ?".

This is the first part of my course on The Fall of the House of Usher. I hope you'll learn things and that you'll want more.

I have other things, from stuff on the British Government to James Joyce and Hopper, so I'll try to keep it interesting.

All the errors (typos, grammatical, vocabulary) are mine.

From the beginning, the narrator seems afraid : the sense of « gloom » (synonym of dejection, despondency, depression, melancholy).

He's surrounded by darkness and shades and finds himself in view of the house of Usher. It makes him uneasy because it has « eyes », like a monster. He is « unnerved », paralized, under the power of the house. It is not the house that frightens him, but he is afraid of what it represents, of its image.

The power of images on the narrator-character is confirmed later, at the end of the paragraph :

« It was possible, (...) and the vacant and eye-like windows. »

==> He's more afraid by what he sees in the tarn around the house. The seese of gloom and melancholy is what is really frightening here.

First introduction of the ghost : « ghastly »

Idea of vacancy keeps up the image of the ghost : in the beginning it is nothing more than an image, a fantasy, born from the reflection of the house on the tarn.

The landscape is not terrible, it becomes terrible because of the ideas we project on it.

« I found myself » : he can't remember how he got here, he's in an unknown place, he's lost, he can't come back home, where he received the letter. He is afraid because he is lost. This is why he is so affected by images.

==> For the moment, nothing is monstruous.

« I know not how it was—but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. »

==> the sense of gloom could have been nulled by feeling poetic sentiments (according to Poe, poetic sentiment is « what is forged in the crucible of imagination »)

The creative power of imagination is reminiscent of the creative power of the Divine. In that sense, the poetic sentiment is what goes beyond the appearance of things to touch their substance, their essence.

This is connected with imagination. He tells us what he feels : compares it with what an opium eater when the effects of the product has venished : the analogy implies hallucination. His fear, his melancholy, is not founded, is not consistent.

« A thing is consistent in the ratio of it's truth, true in the ratio of it's consistency » (Poe)

What the character feels has no consistence, therefore it can't be true. The goading of imagination can change anything into something Sublime / Divine.

So the narrator is afraid, but gives us keys to understand that the story is nothing but a story of images and point of view :

« a mere different arrangement of the particulars of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps to annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression »

==> It is only his point of view, it is personnal, it can be changed. He tells us a shift in the point of view might have provided another arrangement in the elements of the scene.

Scene : dramatic sense of the word, he talks about a representation, a painting (« the details of the picture »). How could you be afraid of a picture ? He is afraid by style, aesthetics, form, manner, composition, not by facts.

The text begins with an opressed narrator, and the idea is pursued and reinforced by the fact that he feels an utter depression of the soul.

But his fancies are said to be shades, shadows, and are, by defnition, images. There is nothing but an appearance, a ghostly and ghastly one : the viewing of a ghost.

From the first paragraph, Poe gives us the keys not to be trapped in what seems to be a Gothic, frightening story.

« The melancholic house » : the melancholic character is the one that has turned it's back on the Divine, on what is supposed to be Truth, Eternal, Sublime, by believing that he could reach sublimity without the Divine.

-> John Keats, « Ode to Melancholy » :

« It dwells with beauty, beauty that must die

And joy, whose hands is ever at his lips.

(...)

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.»

3 figures of speech :

-an Antanaclasis : rhetorcal figure. Repetition of the same word with 2 diff. Meanings. HERE : Reflected. (« I reflected, that a mere different arrangement »)

Reflected : « I thought » + reflection of a mirror. Reflection is frightening.

Since this story bathes withs a specular atmosphere : « I reflected » may also imply that his reflections are nothing but the effect of the landscape on him. We understand his reflections have been infected by the effect of teh reflection on himself.

From the beginning, the landscape has a power on him. This power is shown by the sencond figure of speech.

-A Paragmenon : the repetition of words which derive from the same root.

« oppressed, depressed, impressed » : a process of submission. « Opressed » by the clouds. The idea of a weight on his shoulders. « Depressed » : a depression of the soul, ethymologically « to press down ». What is pressed down ? The soul of the narrator is pressed down by the reflections, the landscape, the shadows.

A sorrowful « impression » : what's pressing so strong on you, it gets into you. It « pervedes » , invades the narrator. It leads us to the idea that the narrator is possessed by these feelings, all the more possessed that his fancies « unnerved » him. (deprived him of his energy)

Before having met Usher, he is already infected by his malady, his melancholy. (« It dwells with Beauty » : a human beauty, far away from the one of God)

-An Anaphora : The same word repeated at the beginning of a line / repetition of the same word.

==> The sense of the passage : its procedure

==> The status of the narrator.

An angel seated, looking in front of him, with empty eyes. He is surrounded by scattered objects, with a dog ? These objects are objects of Human knowledge, referring to the passing of time. They have been thrown because they are useless.

The Angel has lost the harmony and the order of God. (The bat flies, not the Angel). This knowledge has abandonned and been abandonned by God. It is not going to give the truth, the Beauty, the Hamony, the knowledge of existence / life.

The Angel is a fallen Angel.

The Melancholy is emerging from Usher himself. (« I can't alleviate the melancholy of my friend ») What is applied to the mansion originates from its master. The mansion and the master are characterized in the same way because they are the same.

The melancholy is what depresses, opresses and impresses the narrator. It's a downward movement. This is coherent with the physical moment of the narrator, who's riding down at the bottom of the valley to join the House.

The narrator is presented as the phenomenological subject of the narrative.

Upon : synonym of Under. The narrator will not be dominating, but dominated, influenced by the landscape, and therefore won't be an object, but a subject. The common life is falling.

The problem of Usher is a problem of God (Consenguinity : « a single line of descent »)

I hope you liked that first part, and that it's not too confusing. Second part to come soon !

I just seemed to me that it could be interesting to share that kind of things, so I told myself "why not ?".

This is the first part of my course on The Fall of the House of Usher. I hope you'll learn things and that you'll want more.

I have other things, from stuff on the British Government to James Joyce and Hopper, so I'll try to keep it interesting.

All the errors (typos, grammatical, vocabulary) are mine.

From the beginning, the narrator seems afraid : the sense of « gloom » (synonym of dejection, despondency, depression, melancholy).

He's surrounded by darkness and shades and finds himself in view of the house of Usher. It makes him uneasy because it has « eyes », like a monster. He is « unnerved », paralized, under the power of the house. It is not the house that frightens him, but he is afraid of what it represents, of its image.

The power of images on the narrator-character is confirmed later, at the end of the paragraph :

« It was possible, (...) and the vacant and eye-like windows. »

==> He's more afraid by what he sees in the tarn around the house. The seese of gloom and melancholy is what is really frightening here.

First introduction of the ghost : « ghastly »

Idea of vacancy keeps up the image of the ghost : in the beginning it is nothing more than an image, a fantasy, born from the reflection of the house on the tarn.

The landscape is not terrible, it becomes terrible because of the ideas we project on it.

« I found myself » : he can't remember how he got here, he's in an unknown place, he's lost, he can't come back home, where he received the letter. He is afraid because he is lost. This is why he is so affected by images.

==> For the moment, nothing is monstruous.

« I know not how it was—but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. »

==> the sense of gloom could have been nulled by feeling poetic sentiments (according to Poe, poetic sentiment is « what is forged in the crucible of imagination »)

The creative power of imagination is reminiscent of the creative power of the Divine. In that sense, the poetic sentiment is what goes beyond the appearance of things to touch their substance, their essence.

This is connected with imagination. He tells us what he feels : compares it with what an opium eater when the effects of the product has venished : the analogy implies hallucination. His fear, his melancholy, is not founded, is not consistent.

« A thing is consistent in the ratio of it's truth, true in the ratio of it's consistency » (Poe)

What the character feels has no consistence, therefore it can't be true. The goading of imagination can change anything into something Sublime / Divine.

So the narrator is afraid, but gives us keys to understand that the story is nothing but a story of images and point of view :

« a mere different arrangement of the particulars of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps to annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression »

==> It is only his point of view, it is personnal, it can be changed. He tells us a shift in the point of view might have provided another arrangement in the elements of the scene.

Scene : dramatic sense of the word, he talks about a representation, a painting (« the details of the picture »). How could you be afraid of a picture ? He is afraid by style, aesthetics, form, manner, composition, not by facts.

The text begins with an opressed narrator, and the idea is pursued and reinforced by the fact that he feels an utter depression of the soul.

But his fancies are said to be shades, shadows, and are, by defnition, images. There is nothing but an appearance, a ghostly and ghastly one : the viewing of a ghost.

From the first paragraph, Poe gives us the keys not to be trapped in what seems to be a Gothic, frightening story.

« The melancholic house » : the melancholic character is the one that has turned it's back on the Divine, on what is supposed to be Truth, Eternal, Sublime, by believing that he could reach sublimity without the Divine.

-> John Keats, « Ode to Melancholy » :

« It dwells with beauty, beauty that must die

And joy, whose hands is ever at his lips.

(...)

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.»

3 figures of speech :

-an Antanaclasis : rhetorcal figure. Repetition of the same word with 2 diff. Meanings. HERE : Reflected. (« I reflected, that a mere different arrangement »)

Reflected : « I thought » + reflection of a mirror. Reflection is frightening.

Since this story bathes withs a specular atmosphere : « I reflected » may also imply that his reflections are nothing but the effect of the landscape on him. We understand his reflections have been infected by the effect of teh reflection on himself.

From the beginning, the landscape has a power on him. This power is shown by the sencond figure of speech.

-A Paragmenon : the repetition of words which derive from the same root.

« oppressed, depressed, impressed » : a process of submission. « Opressed » by the clouds. The idea of a weight on his shoulders. « Depressed » : a depression of the soul, ethymologically « to press down ». What is pressed down ? The soul of the narrator is pressed down by the reflections, the landscape, the shadows.

A sorrowful « impression » : what's pressing so strong on you, it gets into you. It « pervedes » , invades the narrator. It leads us to the idea that the narrator is possessed by these feelings, all the more possessed that his fancies « unnerved » him. (deprived him of his energy)

Before having met Usher, he is already infected by his malady, his melancholy. (« It dwells with Beauty » : a human beauty, far away from the one of God)

-An Anaphora : The same word repeated at the beginning of a line / repetition of the same word.

==> The sense of the passage : its procedure

==> The status of the narrator.

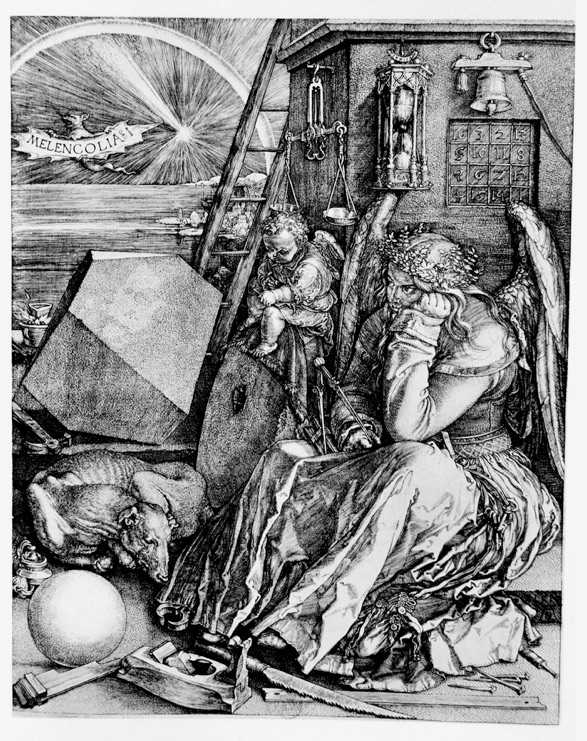

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia.

An angel seated, looking in front of him, with empty eyes. He is surrounded by scattered objects, with a dog ? These objects are objects of Human knowledge, referring to the passing of time. They have been thrown because they are useless.

The Angel has lost the harmony and the order of God. (The bat flies, not the Angel). This knowledge has abandonned and been abandonned by God. It is not going to give the truth, the Beauty, the Hamony, the knowledge of existence / life.

The Angel is a fallen Angel.

The Melancholy is emerging from Usher himself. (« I can't alleviate the melancholy of my friend ») What is applied to the mansion originates from its master. The mansion and the master are characterized in the same way because they are the same.

The melancholy is what depresses, opresses and impresses the narrator. It's a downward movement. This is coherent with the physical moment of the narrator, who's riding down at the bottom of the valley to join the House.

The narrator is presented as the phenomenological subject of the narrative.

Upon : synonym of Under. The narrator will not be dominating, but dominated, influenced by the landscape, and therefore won't be an object, but a subject. The common life is falling.

The problem of Usher is a problem of God (Consenguinity : « a single line of descent »)

I hope you liked that first part, and that it's not too confusing. Second part to come soon !

jeudi 15 mai 2014

My essay on Shakespeare

Now that I have handed it, I can share my essay on Shakespeare's Much Ado without any problems (I think.)

This also means I'm on vacations, so I'll try to post more often.

Warning : this is a first year of college essay. It's not perfect, and there will be errors (grammatical ones, vocabular ones...) and typos. Anyway, I hope it will bring something to the ones who will read it.

“I love you with so much of my heart that none is left to protest.” Says Beatrice to Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing’s first scene of the fourth act. It shows how deep her feelings for him are and how strong their future relationship will be.

The title of «Much Ado About Nothing» draws attention to the so called unseriousness of the play. It’s subjective, much like love, and shows the struggle it engenders to get to marriage. This title also implies comedy, and in a way, some fun made of current life situations and encourages some sort of reconciliation with nature and with ourselves.

Through the different struggles the two couples we are going to study go through, we also understand that the title highlights the efforts that are to be made and the fragility that comes from them.

We are going to study the two couples formed by Benedick and Beatrice and Claudio and Hero through three scenes that seem to most show their differences. It will allow us to show the differences between those two couples.

In the first part, we are going to see the first scene of the first act, with onomastics and the most basic difference between our two couples. In the second part, we’ll study the first scene of the fourth act and the themes of illusion, reality and gender issues. In the third and last part, we are going to look more into the first scene of the fifth act, the true faces of the characters and the theme of jealousy and honor.

In the first scene, we discover two very different pairs of lovers-to-be.

Benedick's name means « he who is to be blessed », while Beatrice's means « she who blesses ». That could indicate that they are meant for each other. Their love is what we could define by «built love». They knew each other before the beginning of the play, and it is hinted that they already tried to have a romantic relationship.

Benedick has an ironic sense of himself. His openness about himself and his self dramatisation show that he is insecure about who he is and makes him accessible.

He is the prototype of the man who scorns love and that courts ladies.

Benedick 's dislike seems to be not of women, but of their treat to the male freedom, privilege and honour. Although he complains of the agitation that Beatrice causes, it is evident that there is some affinity between them, and this is understandable, because she has herself a man's wit and cures his fear of stagnation by challenging him.

When asked by Claudio what he thinks about Hero, he answers « Do you question me as an honest man (…) or as a professed tyrant of their sex ? ». It can be a proof that his disdain for love and women is a pose to protect himself and amuse his friends. Therefore, his falling for Beatrice is no surprise.

After Hero's rejection at the altar, he goes to Beatrice and asks her « Have you wept all this while ? » (IV.1). He shows her respect and sympathy and proves that love has softened his heart. The way he confesses his feelings to Beatrice (« I do love nothing in the world so well as you – is it not strange ? » IV.1) shows a hidden dignity, wonder and makes him almost look like a child.

Beatrice attracts Benedick's attention with a « nobody marks you » (I.1). Nobody does, except her. She resents Benedick's inconsistancy : he had « lent » his heart to her and « won » hers with « false dice » (II.1). That shows they already tried to be a couple.

In the third act (III.2), an iambic pentameter foretells Beatrice's and Benedick's future relationship. She says « Stand I condemned for pride and scorn so much ? (…) Taming my wild heart in thy loving hand ». It shows she is willing to let her love for Benedick soften her.

Beatrice, after her cousin's rejection, is torn between her grief to Hero's situation and her joy from Benedick's love. She then asks him to avenge her cousin : it is to have a proof that Benedick's love is true and that he is worthy of her love. To her, love is not playing roles (as it seems to be for Claudio), it is about companionship ans commitment. She keeps him from kissing her until she is sure he has challenged Claudio : they seem to be already married. They are « too wise to woo peacefully », and their antagonism helps them keep in touch with their feelings.

Beatrice and Benedick hurt themselves in their war of wit because it contradicted their true feelings. In a way, their love surpasses Claudio's and Hero's in its wit, openness and emotional and intellectual vitality. The play ends with them instead of Hero and Claudio, because their honesty about themselves and their feelings assure us that their love will constantly be reaffirmed.

In contrary to Beatrice and Benedick, Hero and Claudio’s love could be qualified as «instant». They don’t know each other and get engaged before Hero has even one talk with her husband-to-be. Unlike Beatrice and Benedick, their names show no compatibility : Claudio's name comes from the Latin « Claudius » that means « lame, crippled ». In Greek mythology, Hero is a priestess of Aphrodite loved by a man named Leander. Elizabethan audiences were accustomed to Hero as a female character because of that story. Shakespeare plays on the name as a male ideal of virtue and strengh, and invites us to see Claudio’s love for Hero as a narcissic projection of his own ideal. This is why, for her sake and Claudio’s, she had to die. By losing the illusion he projected upon her, she gains her reality.

Hero and Claudio's relationship shows extreme shyness and reticence and is lanced with extreme conventionality. Hero's beauty strikes Claudio and leaves him speechless until he is alone with Benedick.

Claudio wants to succeed. He dreams of glory and heroism, and in peace, Hero is a trophy worthy of what he hopes will be his destiny. He idealized himself, which denies him self-knowledge, and idealising Hero may mask his fear and heatred of women.

The fact that Don Pedro charms Hero into her marriage with Claudio says much about his fear, his emotional insecurity and his social ambition.

After Don John told Claudio Hero was disloyal to him, the young man declares « ...there I will shame her » (III.2). His denunciation seems to come from a personal insecurity that causes him to think honour is the most important thing and suggests that he already conviced Hero as guilty before even facing her.

He takes control of the marriage ceremony and is arrongant and hurtful towards Hero and Leonato, telling the old man to « Give not this rotten orange to your old friend » (IV.1)

The fact that Claudion compares Hero, first to Diana and then to Venus, two very different Goddesses, shows that he can't face her imperfection.

The bad opinion we have of Claudio is reinforced by his actions after Hero has been declared dead. He jokes « We had like to have had our two noses snapped off with two old men without teeth » (V.1), and then tried to have Benedick into a banter, who insults him in response.

Claudio's only redemption is possible because of his youth and repentance. He is still blinded by Hero's outward beauty and reputation, but his apology to Leonato seems sincere (« Yet sinned I not / But in mistaking »). His amazement at the reapparition of Hero seem genuine (« Antoher Hero ? »)

Hero's reticence to her marriage with Claudio is a sign both of innocence and of her wealth and social position.

Among her female friends, she shows quite a flexible wit. Her part in the plan to get Beatrice and Benedick together give her character a new depth. Immediately before her wedding, she plays with her dress to keep her mind out of her anxiety.

She seems very conventionnal and deserving of sympathy. She is defenceless against Claudio's accusations, and stays dign until she faints. She is even more elevated by Beatrice and the Friar taking her defence, as well as by the hard time she has understanding what she is accused of.

The fact that she is still willing to marry Claudio after he has treated her so poorly is strange, but it sticks to her character of a conventionnal heroine.

Our study of the two couples show that they are complementaries. We could say that Beatrice and Benedick's story rises from it and complements it. Beatrice and Benedick bring wit and repartee, while Claudio lacks wit and behaves conventionnally and Hero is obedient and hardly speaks.

We are now going to see more of the differences between our couples, and the themes of Illusion, reality, reputation and gender issues, mainly through the first scene of the fourth act.

Claudio's rejection of Hero and the reaction of her father in the first scene of the fourth act point some gender-related issues in the play. It also highlights the theme of illusion and reality, which is very present through the play.

The gender and reputation related issues appear through all the play, but are made easily seen by Claudio’s reaction to Hero’s so called disloyalty. He announces «If I see anything to-night why I should not marry her / to-morrow, in the congregation where I should wed, there will I shame her.» (III.2) This is particularly nasty of him. Rather than just canceling the wedding if Hero is disloyal, he’s determined on disgracing her in front of the whole assembly. His plan is more about vengefully ruining her reputation than it is about escaping a loveless, dishonest marriage. Then, at the altar, he rejects Hero using mean and hurtful words, calling her sarcasticly an « rich and precious gift » (IV.1), and telling Leonato to « Give not this rotten orange to your friend / She's but the sign and semblance of her honour». He accompanies his words by giving Hero's hand back to her father and throwing her to the floor, before playing on the words « Oh, Hero ! What a hero hadst thoust been (…) and counsels of thy heart ?». It shows that his vision of her dishonour is as illusory as his love.

Claudio then uses Leonato to make his point. He asks the older man to make Hero tell the truth, and Leonato complies. We then understand that no one will stand for Hero, and that what is happening is a matter of pride and reputation («Claudio : Let me but move one question to your daughter, / And by that fatherly and kindly power / That you have in her, bid her answer truly. / Leonato : I charge thee do so, as thou art my child. / Hero : O, God defend me! How am I beset! / What kind of catechising call you this? (IV.1)») This is a difficult passage to read, as it’s the first instance where Leonato chooses Claudio’s word over his daughter’s. He demands that Hero answer Claudio’s question, indicating that he’s already trusting Claudio instead of defending his daughter. Ultimately, this episode is sickening because of our intuition that Leonato’s role – because he knows his daughter and her honor– is to stand up for her, not to indulge Claudio in this public spectacle. Hero’s reputation is on the line, and in the end, as a woman, her word isn’t worth much against a man’s. This episode reminds us of the constant cuckoldry jests in the play. Though they were jokes, they seriously refer to the distrust men had for their wives, and we could bet it also makes them hesitate to stand up for their daughters.

Leonato’s reaction is not long-waited for. As he believes everything Claudio says, and instead of standing for his daughter, he sides with Claudio, adding that he regrets she is his daughter («I might have said, 'No part of it is mine; / This shame derives itself from unknown loins'? / (...) / And salt too little which may season give / To her foul tainted flesh! (IV.1)»)

Leonato does not grieve for the apparent death of his only child; rather, he rejoices over it as the best way to hide her shame (and therefore his shame). This leads him to reveal that his wounded pride is what he’s really worried about. He wishes she was not his flesh and blood, but some adopted child, so he could say, "No part of this scandal is mine," and renounce the girl without any grief. It’s clear from Leonato’s words that he is more concerned about his own hurt pride than Hero’s dishonor.

But when it is made clear that they were mislead by Don John, Claudio hurries to preach his love for the vertuous Hero. («Sweet Hero, now thy image doth appear / In the rare semblance that I lov'd it first. (V.1)»)

He declares his love for Hero again as soon as he hears of her innocence. His sudden renewed love of Hero makes us feel as though his love is not actually as deep as we’d want it to be; his love was destroyed by outside circumstance and is resolved by outside circumstance too. We wonder whether Claudio will be able to bear other miscommunications when the pair is married – or if he will be as quick to judge as he is currently, even if he’s wrong.

In this scene, no one could differ more from Claudio than Benedick. When Claudio’s love for Hero collapses and turns to dust while facing adversity, Benedick’s love for Beatrice gets stronger and helps him grow into the man he thinks is right for Beatrice.

He first enquires about Hero, asking the Friar and Beatrice «How doth the lady?» (IV.1).

This is a monumental transformation for him. As Don Pedro, Don John, and Claudio storm out, Benedick surprisingly stays behind. While this is an obvious indication that Benedick’s allegiances may have changed, it seems there is some deeper transformation at work (perhaps regarding his love for Beatrice, but perhaps also his sense of justice).

He then comforts Beatrice and pledges his love for her. Their relationship is cemented by Hero's suffering. He goes to Beatrice and asks her « ...have you wept all this while ?» before telling her that he « do love nothing in the world so well as (her) ». It distances him with Claudio : while one of the men hurts the woman he is supposed to love, the other comforts her and assures her of his love. Asking Beatrice to « Come bid me do anything for (her)», Benedick takes the place of the conventionnal lover, and her answer to « Kill Claudio », she makes him commit himself to his feelings rather than the male code that made all the other men selfish, unfeeling and hypocritcal.

Left alone with no other witness than Benedick, Beatrice storms about not being able to avenge her cousin because she is not a man («O that I were a man for his sake ! or that I had any friend would be a man for my sake!» IV.1). Beatrice berates all men for being wimps. If Benedick didn’t understand before, he does now: Beatrice needs a manly man. She rails against what manliness has come to in these days of courtly pomp, and it’s not a flattering picture. It’s interesting that Benedick has spent all this time up to now indulging in similar rantings against all the courtly niceties of love (using Claudio as a prime example). Now that Benedick has fallen in love, he’s provided a chance to prove that he’s different from other lovers who were transformed by love into sighing idiots (like Claudio). Especially now that Claudio has turned out to be faithless and cruel, Benedick can show that there are different ways to love than the stupid courtly formalities, which he’s not good at anyway. This could be Benedick’s big chance to win Beatrice’s heart.

Now that we have studied the proeminent themes of the first scene of the fourth act, we are going to see that the first scene of the following act brings up the true face of the characters, as well as the themes of jealousy, honour and noting.

In the first scene of the fifth act, Leonato begins to think that his daughter was framed. When Claudio and Don Pedro enter the scene, he loses his temper and accuses them to have wasted and challenges him to a duel. Claudio disdainfully refuses and jokes as the old men leave. Benedick enters, refuses Claudio's companionship and challenges him.

While Claudio and Don Pedro keep their composure facing the old men, they seem ridiculous. As Benedick enters, Claudio's joke : « We had like to have our noses snapped off by two old men without teeth » (V.1) ( To Leonato’s face, Claudio makes a big show of respecting his age, but it’s clear from this comment that Claudio is not exactly Mr. Reverence. Age doesn’t seem to command respect for Claudio; he approaches it more as a weakness than a reason for reverence, which is pretty immature of him. It’s another strike against Claudio’s character.)

, and Don Pedro's answer « I doubt we should have been too young for them », show how arrogant and mean they are. Their disdain towards Hero's fate and Leonato's pain, even if he's supposed to be their friend,

As Benedick enters, the sympathy we could have felt for his friends vanishes with their prompt way to insult Leonato and Antonio so soon after Hero’s death. It takes a long moment for Claudio and Don Pedro to realize something is wrong with Benedick - whose transformation to Beatrice’s champion helped grow and changed. He keeps his promise to her, challenging Claudio and choosing to part from his friends («Benedick : My lord, for your many / courtesies I thank you. I must discontinue your company.» (V.1))

This is a decisive move for Benedick; as it is the moment when he explicitly breaks company with Don Pedro shows a public transformation in his allegiance.

He leaves on a «I will leave you to your gossip-like humour» (V.1) both shows his moral growth and distances him even further from his friends.

Don Pedro and Claudio remain arrogant and insensitive until the end. In his words «I know not how to pray your patience; / Yet I must speak. Choose your revenge yourself; / Impose me to what penance your invention / Can lay upon my sin. Yet sinn'd I not / But in mistaking.(V.1)», Claudio is saying something unacceptable. He has just found out he wrongfully accused Hero and he thinks he caused her death. Instead of just hanging his head in shame and being sorry, he feels the need to point out that he was misled, so none of this was really his fault. It seems Claudio is more concerned with protecting his pride than mourning over his part in Hero’s death. Even that he’s willing to submit himself to punishment seems more about the appropriate formalities of dealing with his wrong than any actual regret or repentance he has. Claudio then takes pride and flatters himself in marrying an heiress he has never seen and whose only quality is her wealth, saying «I’ll hold my mind were she an Ethiop» (V.4), meaning that he'll stick to his promise, no matter what his new bride looks likes. "Ethiope" was a term for any black person, and black was considered to the opposite of beautiful. It strenghtens the argument that he is nothing more than a materialist, even after the act of penance he had to do to regain Leonato’s trust.

Honour is important in the play. It hinges on it, because of Hero’s disgrace and redemption. A woman’s honour is based upon virginity before marriage (which is why the reactions to Hero’s so called treason are so violent), while a man’s honour is based on his valour in a fight.

However, it seems like Beatrice is the one that has the more honour. In friendship and love, it demands loyalty, and this is why she asks Benedick to avenge Hero’s dishonour as if it were her own. She exposes the gap between the illusions we have of honour and the reality, and her attack upon Claudio’s behavior exposes his heartlessness and hypocrisy. She then goes on to Benedick’s unwillingness to grant her her request to challenge Claudio («You dare easier be friends with me than fight with mine enemy» IV.1). She argues against the male solidarity, which is central to their code of honour, and shows Benedick he should be putting mutual feelings before standards of conduct. And by taking up her challenge, he follows his conscience instead of a code, which helps him grow in moral stature.

The major complication in the play comes from Claudio’s denunciation of Hero, which is itself based on a misconception, a trick, which is virtually nothing. The minor one is a lie that unites Beatrice and Benedick. While one separates Hero and Claudio, the other is quickly forgotten : Beatrice and Benedick are aware of their love for each other, and it doesn’t matter to them that a lie made them act on their feelings.

Spying and eavesdropping are important in the play. If Claudio and Don Pedro had not spied on who the mistook for Hero, the wedding would have happened, and if Beatrice and Benedick had not eavesdropped, they wouldn’t have faced their love for each other. In the first scene of the play, Claudio asks Benedick he he has «noted the daughter of Signor Leonato», to which he replies «I noted her not, but I looked on her». He points out that perception is subjective. If beauty is an illusion, the lover’s feelings will change even if the object of his feelings stay the same.

Beatrice and Benedick discover their feelings away from the others, and when Benedick commits himself to Beatrice, he breaks through the illusion, leading to his discovery of himself and his ability to change. Their love began in an illusory antagonism and was sealed in violence with Beatrice’s demand of Claudio’s death, but it connects them to what is more permanent than the situation they find themselves in. The openness of their relationship, and the realism they add to it get it rid of any form of jealousy.

Claudio’s idealized love for Hero masked fear and violence, which erupted during the first wedding ceremony. His jealousy reminds of Othello, a fearless and resourceful man in battle, but easily undone by love, and he puts Hero on such a high pedestal he’s incapable to woo her himself

He is incapable to love correctly until his idealisations were shattered. His song and epitaph for Hero show a process of remorse. He learns that love is unchanging, as well as the meaning of true love, and is finally fit to have Hero coming back to him.

To conclude, we could say that two quotes perfectly sum up the two couples we have studied. The first is from the first scene of the second act, where Claudio says : «Lady, as you are mine, I am yours: I give away myself for / you and dote upon the exchange.»

Claudio’s declaration to Hero could show, in his choice of words, how little love truly means to him. «Mine» and «yours» implie possession, while «give away myself» means that he feels he has more value than she does. «To dote» means showing love for something or someone and look past its flaws, which he won’t do for Hero, and «exchange» is not the kind of word that is likely to be heard in a love declaration, because of it’s commercial connotations (which could mean that he sees Hero only as a mean to rise to a higher social status).

In comparison, the second quote (Benedick’s «I do love nothing in the world so well as you- is not that strange?») from the frist scene of act four, and which is prompted by Beatrice’s need of a man to challenge Claudio, shows that he offers his love as proof that he’d do any task for her. They then compromise not to «woo peacefully», which show the future balance their relationship will reach, and prove that it is the image of what true love should be.

Sources :

-Movies : Much Ado About Nothing (both BBC’s 1984 and Kenneth Brannagh’s 1993 versions)

-Much Ado About Nothing (Oxford School edition)

-Much Ado About Nothing (York Notes Advanced)

This also means I'm on vacations, so I'll try to post more often.

Warning : this is a first year of college essay. It's not perfect, and there will be errors (grammatical ones, vocabular ones...) and typos. Anyway, I hope it will bring something to the ones who will read it.

“I love you with so much of my heart that none is left to protest.” Says Beatrice to Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing’s first scene of the fourth act. It shows how deep her feelings for him are and how strong their future relationship will be.

The title of «Much Ado About Nothing» draws attention to the so called unseriousness of the play. It’s subjective, much like love, and shows the struggle it engenders to get to marriage. This title also implies comedy, and in a way, some fun made of current life situations and encourages some sort of reconciliation with nature and with ourselves.

Through the different struggles the two couples we are going to study go through, we also understand that the title highlights the efforts that are to be made and the fragility that comes from them.

We are going to study the two couples formed by Benedick and Beatrice and Claudio and Hero through three scenes that seem to most show their differences. It will allow us to show the differences between those two couples.

In the first part, we are going to see the first scene of the first act, with onomastics and the most basic difference between our two couples. In the second part, we’ll study the first scene of the fourth act and the themes of illusion, reality and gender issues. In the third and last part, we are going to look more into the first scene of the fifth act, the true faces of the characters and the theme of jealousy and honor.

In the first scene, we discover two very different pairs of lovers-to-be.

Benedick's name means « he who is to be blessed », while Beatrice's means « she who blesses ». That could indicate that they are meant for each other. Their love is what we could define by «built love». They knew each other before the beginning of the play, and it is hinted that they already tried to have a romantic relationship.

Benedick has an ironic sense of himself. His openness about himself and his self dramatisation show that he is insecure about who he is and makes him accessible.

He is the prototype of the man who scorns love and that courts ladies.

Benedick 's dislike seems to be not of women, but of their treat to the male freedom, privilege and honour. Although he complains of the agitation that Beatrice causes, it is evident that there is some affinity between them, and this is understandable, because she has herself a man's wit and cures his fear of stagnation by challenging him.

When asked by Claudio what he thinks about Hero, he answers « Do you question me as an honest man (…) or as a professed tyrant of their sex ? ». It can be a proof that his disdain for love and women is a pose to protect himself and amuse his friends. Therefore, his falling for Beatrice is no surprise.

After Hero's rejection at the altar, he goes to Beatrice and asks her « Have you wept all this while ? » (IV.1). He shows her respect and sympathy and proves that love has softened his heart. The way he confesses his feelings to Beatrice (« I do love nothing in the world so well as you – is it not strange ? » IV.1) shows a hidden dignity, wonder and makes him almost look like a child.

Beatrice attracts Benedick's attention with a « nobody marks you » (I.1). Nobody does, except her. She resents Benedick's inconsistancy : he had « lent » his heart to her and « won » hers with « false dice » (II.1). That shows they already tried to be a couple.

In the third act (III.2), an iambic pentameter foretells Beatrice's and Benedick's future relationship. She says « Stand I condemned for pride and scorn so much ? (…) Taming my wild heart in thy loving hand ». It shows she is willing to let her love for Benedick soften her.

Beatrice, after her cousin's rejection, is torn between her grief to Hero's situation and her joy from Benedick's love. She then asks him to avenge her cousin : it is to have a proof that Benedick's love is true and that he is worthy of her love. To her, love is not playing roles (as it seems to be for Claudio), it is about companionship ans commitment. She keeps him from kissing her until she is sure he has challenged Claudio : they seem to be already married. They are « too wise to woo peacefully », and their antagonism helps them keep in touch with their feelings.

Beatrice and Benedick hurt themselves in their war of wit because it contradicted their true feelings. In a way, their love surpasses Claudio's and Hero's in its wit, openness and emotional and intellectual vitality. The play ends with them instead of Hero and Claudio, because their honesty about themselves and their feelings assure us that their love will constantly be reaffirmed.

In contrary to Beatrice and Benedick, Hero and Claudio’s love could be qualified as «instant». They don’t know each other and get engaged before Hero has even one talk with her husband-to-be. Unlike Beatrice and Benedick, their names show no compatibility : Claudio's name comes from the Latin « Claudius » that means « lame, crippled ». In Greek mythology, Hero is a priestess of Aphrodite loved by a man named Leander. Elizabethan audiences were accustomed to Hero as a female character because of that story. Shakespeare plays on the name as a male ideal of virtue and strengh, and invites us to see Claudio’s love for Hero as a narcissic projection of his own ideal. This is why, for her sake and Claudio’s, she had to die. By losing the illusion he projected upon her, she gains her reality.

Hero and Claudio's relationship shows extreme shyness and reticence and is lanced with extreme conventionality. Hero's beauty strikes Claudio and leaves him speechless until he is alone with Benedick.

Claudio wants to succeed. He dreams of glory and heroism, and in peace, Hero is a trophy worthy of what he hopes will be his destiny. He idealized himself, which denies him self-knowledge, and idealising Hero may mask his fear and heatred of women.

The fact that Don Pedro charms Hero into her marriage with Claudio says much about his fear, his emotional insecurity and his social ambition.

After Don John told Claudio Hero was disloyal to him, the young man declares « ...there I will shame her » (III.2). His denunciation seems to come from a personal insecurity that causes him to think honour is the most important thing and suggests that he already conviced Hero as guilty before even facing her.

He takes control of the marriage ceremony and is arrongant and hurtful towards Hero and Leonato, telling the old man to « Give not this rotten orange to your old friend » (IV.1)

The fact that Claudion compares Hero, first to Diana and then to Venus, two very different Goddesses, shows that he can't face her imperfection.

The bad opinion we have of Claudio is reinforced by his actions after Hero has been declared dead. He jokes « We had like to have had our two noses snapped off with two old men without teeth » (V.1), and then tried to have Benedick into a banter, who insults him in response.

Claudio's only redemption is possible because of his youth and repentance. He is still blinded by Hero's outward beauty and reputation, but his apology to Leonato seems sincere (« Yet sinned I not / But in mistaking »). His amazement at the reapparition of Hero seem genuine (« Antoher Hero ? »)

Hero's reticence to her marriage with Claudio is a sign both of innocence and of her wealth and social position.

Among her female friends, she shows quite a flexible wit. Her part in the plan to get Beatrice and Benedick together give her character a new depth. Immediately before her wedding, she plays with her dress to keep her mind out of her anxiety.

She seems very conventionnal and deserving of sympathy. She is defenceless against Claudio's accusations, and stays dign until she faints. She is even more elevated by Beatrice and the Friar taking her defence, as well as by the hard time she has understanding what she is accused of.

The fact that she is still willing to marry Claudio after he has treated her so poorly is strange, but it sticks to her character of a conventionnal heroine.

Our study of the two couples show that they are complementaries. We could say that Beatrice and Benedick's story rises from it and complements it. Beatrice and Benedick bring wit and repartee, while Claudio lacks wit and behaves conventionnally and Hero is obedient and hardly speaks.

We are now going to see more of the differences between our couples, and the themes of Illusion, reality, reputation and gender issues, mainly through the first scene of the fourth act.

Claudio's rejection of Hero and the reaction of her father in the first scene of the fourth act point some gender-related issues in the play. It also highlights the theme of illusion and reality, which is very present through the play.

The gender and reputation related issues appear through all the play, but are made easily seen by Claudio’s reaction to Hero’s so called disloyalty. He announces «If I see anything to-night why I should not marry her / to-morrow, in the congregation where I should wed, there will I shame her.» (III.2) This is particularly nasty of him. Rather than just canceling the wedding if Hero is disloyal, he’s determined on disgracing her in front of the whole assembly. His plan is more about vengefully ruining her reputation than it is about escaping a loveless, dishonest marriage. Then, at the altar, he rejects Hero using mean and hurtful words, calling her sarcasticly an « rich and precious gift » (IV.1), and telling Leonato to « Give not this rotten orange to your friend / She's but the sign and semblance of her honour». He accompanies his words by giving Hero's hand back to her father and throwing her to the floor, before playing on the words « Oh, Hero ! What a hero hadst thoust been (…) and counsels of thy heart ?». It shows that his vision of her dishonour is as illusory as his love.

Claudio then uses Leonato to make his point. He asks the older man to make Hero tell the truth, and Leonato complies. We then understand that no one will stand for Hero, and that what is happening is a matter of pride and reputation («Claudio : Let me but move one question to your daughter, / And by that fatherly and kindly power / That you have in her, bid her answer truly. / Leonato : I charge thee do so, as thou art my child. / Hero : O, God defend me! How am I beset! / What kind of catechising call you this? (IV.1)») This is a difficult passage to read, as it’s the first instance where Leonato chooses Claudio’s word over his daughter’s. He demands that Hero answer Claudio’s question, indicating that he’s already trusting Claudio instead of defending his daughter. Ultimately, this episode is sickening because of our intuition that Leonato’s role – because he knows his daughter and her honor– is to stand up for her, not to indulge Claudio in this public spectacle. Hero’s reputation is on the line, and in the end, as a woman, her word isn’t worth much against a man’s. This episode reminds us of the constant cuckoldry jests in the play. Though they were jokes, they seriously refer to the distrust men had for their wives, and we could bet it also makes them hesitate to stand up for their daughters.

Leonato’s reaction is not long-waited for. As he believes everything Claudio says, and instead of standing for his daughter, he sides with Claudio, adding that he regrets she is his daughter («I might have said, 'No part of it is mine; / This shame derives itself from unknown loins'? / (...) / And salt too little which may season give / To her foul tainted flesh! (IV.1)»)

Leonato does not grieve for the apparent death of his only child; rather, he rejoices over it as the best way to hide her shame (and therefore his shame). This leads him to reveal that his wounded pride is what he’s really worried about. He wishes she was not his flesh and blood, but some adopted child, so he could say, "No part of this scandal is mine," and renounce the girl without any grief. It’s clear from Leonato’s words that he is more concerned about his own hurt pride than Hero’s dishonor.

But when it is made clear that they were mislead by Don John, Claudio hurries to preach his love for the vertuous Hero. («Sweet Hero, now thy image doth appear / In the rare semblance that I lov'd it first. (V.1)»)

He declares his love for Hero again as soon as he hears of her innocence. His sudden renewed love of Hero makes us feel as though his love is not actually as deep as we’d want it to be; his love was destroyed by outside circumstance and is resolved by outside circumstance too. We wonder whether Claudio will be able to bear other miscommunications when the pair is married – or if he will be as quick to judge as he is currently, even if he’s wrong.

In this scene, no one could differ more from Claudio than Benedick. When Claudio’s love for Hero collapses and turns to dust while facing adversity, Benedick’s love for Beatrice gets stronger and helps him grow into the man he thinks is right for Beatrice.

He first enquires about Hero, asking the Friar and Beatrice «How doth the lady?» (IV.1).

This is a monumental transformation for him. As Don Pedro, Don John, and Claudio storm out, Benedick surprisingly stays behind. While this is an obvious indication that Benedick’s allegiances may have changed, it seems there is some deeper transformation at work (perhaps regarding his love for Beatrice, but perhaps also his sense of justice).

He then comforts Beatrice and pledges his love for her. Their relationship is cemented by Hero's suffering. He goes to Beatrice and asks her « ...have you wept all this while ?» before telling her that he « do love nothing in the world so well as (her) ». It distances him with Claudio : while one of the men hurts the woman he is supposed to love, the other comforts her and assures her of his love. Asking Beatrice to « Come bid me do anything for (her)», Benedick takes the place of the conventionnal lover, and her answer to « Kill Claudio », she makes him commit himself to his feelings rather than the male code that made all the other men selfish, unfeeling and hypocritcal.

Left alone with no other witness than Benedick, Beatrice storms about not being able to avenge her cousin because she is not a man («O that I were a man for his sake ! or that I had any friend would be a man for my sake!» IV.1). Beatrice berates all men for being wimps. If Benedick didn’t understand before, he does now: Beatrice needs a manly man. She rails against what manliness has come to in these days of courtly pomp, and it’s not a flattering picture. It’s interesting that Benedick has spent all this time up to now indulging in similar rantings against all the courtly niceties of love (using Claudio as a prime example). Now that Benedick has fallen in love, he’s provided a chance to prove that he’s different from other lovers who were transformed by love into sighing idiots (like Claudio). Especially now that Claudio has turned out to be faithless and cruel, Benedick can show that there are different ways to love than the stupid courtly formalities, which he’s not good at anyway. This could be Benedick’s big chance to win Beatrice’s heart.

Now that we have studied the proeminent themes of the first scene of the fourth act, we are going to see that the first scene of the following act brings up the true face of the characters, as well as the themes of jealousy, honour and noting.

In the first scene of the fifth act, Leonato begins to think that his daughter was framed. When Claudio and Don Pedro enter the scene, he loses his temper and accuses them to have wasted and challenges him to a duel. Claudio disdainfully refuses and jokes as the old men leave. Benedick enters, refuses Claudio's companionship and challenges him.

While Claudio and Don Pedro keep their composure facing the old men, they seem ridiculous. As Benedick enters, Claudio's joke : « We had like to have our noses snapped off by two old men without teeth » (V.1) ( To Leonato’s face, Claudio makes a big show of respecting his age, but it’s clear from this comment that Claudio is not exactly Mr. Reverence. Age doesn’t seem to command respect for Claudio; he approaches it more as a weakness than a reason for reverence, which is pretty immature of him. It’s another strike against Claudio’s character.)

, and Don Pedro's answer « I doubt we should have been too young for them », show how arrogant and mean they are. Their disdain towards Hero's fate and Leonato's pain, even if he's supposed to be their friend,

As Benedick enters, the sympathy we could have felt for his friends vanishes with their prompt way to insult Leonato and Antonio so soon after Hero’s death. It takes a long moment for Claudio and Don Pedro to realize something is wrong with Benedick - whose transformation to Beatrice’s champion helped grow and changed. He keeps his promise to her, challenging Claudio and choosing to part from his friends («Benedick : My lord, for your many / courtesies I thank you. I must discontinue your company.» (V.1))

This is a decisive move for Benedick; as it is the moment when he explicitly breaks company with Don Pedro shows a public transformation in his allegiance.

He leaves on a «I will leave you to your gossip-like humour» (V.1) both shows his moral growth and distances him even further from his friends.

Don Pedro and Claudio remain arrogant and insensitive until the end. In his words «I know not how to pray your patience; / Yet I must speak. Choose your revenge yourself; / Impose me to what penance your invention / Can lay upon my sin. Yet sinn'd I not / But in mistaking.(V.1)», Claudio is saying something unacceptable. He has just found out he wrongfully accused Hero and he thinks he caused her death. Instead of just hanging his head in shame and being sorry, he feels the need to point out that he was misled, so none of this was really his fault. It seems Claudio is more concerned with protecting his pride than mourning over his part in Hero’s death. Even that he’s willing to submit himself to punishment seems more about the appropriate formalities of dealing with his wrong than any actual regret or repentance he has. Claudio then takes pride and flatters himself in marrying an heiress he has never seen and whose only quality is her wealth, saying «I’ll hold my mind were she an Ethiop» (V.4), meaning that he'll stick to his promise, no matter what his new bride looks likes. "Ethiope" was a term for any black person, and black was considered to the opposite of beautiful. It strenghtens the argument that he is nothing more than a materialist, even after the act of penance he had to do to regain Leonato’s trust.

Honour is important in the play. It hinges on it, because of Hero’s disgrace and redemption. A woman’s honour is based upon virginity before marriage (which is why the reactions to Hero’s so called treason are so violent), while a man’s honour is based on his valour in a fight.

However, it seems like Beatrice is the one that has the more honour. In friendship and love, it demands loyalty, and this is why she asks Benedick to avenge Hero’s dishonour as if it were her own. She exposes the gap between the illusions we have of honour and the reality, and her attack upon Claudio’s behavior exposes his heartlessness and hypocrisy. She then goes on to Benedick’s unwillingness to grant her her request to challenge Claudio («You dare easier be friends with me than fight with mine enemy» IV.1). She argues against the male solidarity, which is central to their code of honour, and shows Benedick he should be putting mutual feelings before standards of conduct. And by taking up her challenge, he follows his conscience instead of a code, which helps him grow in moral stature.

The major complication in the play comes from Claudio’s denunciation of Hero, which is itself based on a misconception, a trick, which is virtually nothing. The minor one is a lie that unites Beatrice and Benedick. While one separates Hero and Claudio, the other is quickly forgotten : Beatrice and Benedick are aware of their love for each other, and it doesn’t matter to them that a lie made them act on their feelings.

Spying and eavesdropping are important in the play. If Claudio and Don Pedro had not spied on who the mistook for Hero, the wedding would have happened, and if Beatrice and Benedick had not eavesdropped, they wouldn’t have faced their love for each other. In the first scene of the play, Claudio asks Benedick he he has «noted the daughter of Signor Leonato», to which he replies «I noted her not, but I looked on her». He points out that perception is subjective. If beauty is an illusion, the lover’s feelings will change even if the object of his feelings stay the same.

Beatrice and Benedick discover their feelings away from the others, and when Benedick commits himself to Beatrice, he breaks through the illusion, leading to his discovery of himself and his ability to change. Their love began in an illusory antagonism and was sealed in violence with Beatrice’s demand of Claudio’s death, but it connects them to what is more permanent than the situation they find themselves in. The openness of their relationship, and the realism they add to it get it rid of any form of jealousy.

Claudio’s idealized love for Hero masked fear and violence, which erupted during the first wedding ceremony. His jealousy reminds of Othello, a fearless and resourceful man in battle, but easily undone by love, and he puts Hero on such a high pedestal he’s incapable to woo her himself

He is incapable to love correctly until his idealisations were shattered. His song and epitaph for Hero show a process of remorse. He learns that love is unchanging, as well as the meaning of true love, and is finally fit to have Hero coming back to him.

To conclude, we could say that two quotes perfectly sum up the two couples we have studied. The first is from the first scene of the second act, where Claudio says : «Lady, as you are mine, I am yours: I give away myself for / you and dote upon the exchange.»

Claudio’s declaration to Hero could show, in his choice of words, how little love truly means to him. «Mine» and «yours» implie possession, while «give away myself» means that he feels he has more value than she does. «To dote» means showing love for something or someone and look past its flaws, which he won’t do for Hero, and «exchange» is not the kind of word that is likely to be heard in a love declaration, because of it’s commercial connotations (which could mean that he sees Hero only as a mean to rise to a higher social status).

In comparison, the second quote (Benedick’s «I do love nothing in the world so well as you- is not that strange?») from the frist scene of act four, and which is prompted by Beatrice’s need of a man to challenge Claudio, shows that he offers his love as proof that he’d do any task for her. They then compromise not to «woo peacefully», which show the future balance their relationship will reach, and prove that it is the image of what true love should be.

Sources :

-Movies : Much Ado About Nothing (both BBC’s 1984 and Kenneth Brannagh’s 1993 versions)

-Much Ado About Nothing (Oxford School edition)

-Much Ado About Nothing (York Notes Advanced)

Inscription à :

Commentaires (Atom)